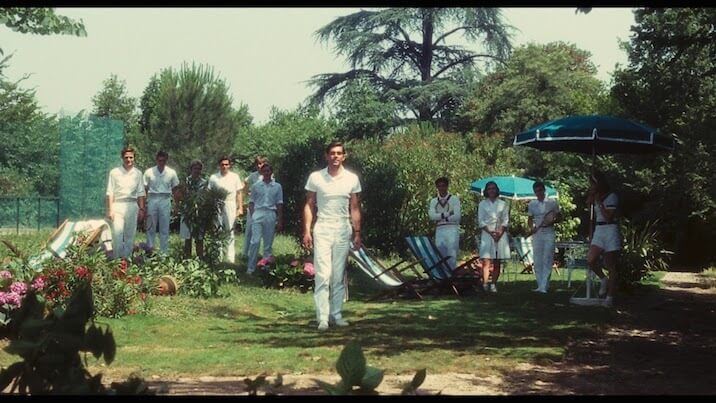

An interview with the librettist of The Garden of The Finzi-Continis.

We spoke to THE GARDEN OF THE FINZI-CONTINIS librettist Michael Korie (Flying Over Sunset, Grey Gardens) about his collaborative relationship with composer Ricky Ian Gordon, the way he approaches adaptation, and the most exciting moments in our upcoming opera. Get the inside scoop before you see the dynamic new work.

What is your history with THE GARDEN OF THE FINZI-CONTINIS? Had you read the novel or seen the movie before approaching the project?

Yes. I saw the movie back when I was in high school, and I was very moved and impressed by it and always remembered it. When the idea was suggested for an opera by Ricky Ian Gordon, I read the book and then I read a new translation of it — two different versions. And I realized there was a lot more content, of course, in the book than was in the movie.

The movie was beautiful. The book had a lot more grit to it. I began to see it as a drama that could be told through music. And it seemed very compelling to have a family that saw only, really, what they wanted to see in their very rarified situation — their beautiful garden, and their villa, as the world around them was changing. And not noticing until it was too late.

That seemed a very apt metaphor for the world we live in today. I felt the world was changing around me. I felt that America was becoming unrecognizable. And I always like to write a work that has a direct connection to the audience, but I don’t like it to be didactic or obvious. I feel that by setting a work in a historical time, people come in expecting to see a historical story. And it’s only part way through that they realize, good gracious. They’re really writing about us today. They’re really writing about these same situations that we live in right now.

I call that writing a stealth opera. It kind of sneaks up on you. And I think it’s very important to work on a level that hits the audience where they live.

I think it’s interesting that you read two different translations before starting to write your adaptation. Could you talk about adaptation as an act of translation?

Well, I read it. And then I put them down. And I try to think about the story through music. The way people speak in novels, or the way novelists describe situations in prose — it’s not just a matter of lifting dialogue out of a book, or putting it into another language and singing it. Book dialogue, novel dialogue, and novelistic description have to be reinvented so that they can be told through music.

And music has its own dramatic parameters. I call it a kind of musical geography. Where, in an opera, it’s like climbing the highest peak of a rollercoaster. It’s going up and up, and the musical values are getting more intense, and the drama’s getting more intense, until you achieve the summit and the curtain comes down and that’s the end of an act. And you’re in a suspenseful situation.

That doesn’t occur in novels. So, what I have to do is familiarize myself with the story, and then start thinking about it through music. What areas can be sung? How can you set things up and lead the audience along on a journey, without explaining so that they don’t get ahead of it? Just implying, inferring, and laying the groundwork for confrontation and conflict to happen.

And so really what I do is I put it all into my own language. There are similarities here and there, where phrases stick with me or that I absolutely want to use because I feel they’re imperative, but, generally, you can’t sing the dialogue in a book! A lot of times they say, “That’s right!” or “Yes!” All of the content is told in prose. So it all has to be rethought.

But there’s no question that the two different translations — one more formalistic, and the one more contemporary — were a great help.

We also played up certain aspects of the story that were not in the novel. The character of Alberto — his gayness, for example. There were scenes where Alberto appeared, the subtext was there, but there was no content. So I read other stories by Bassani, and reinvented, and fleshed him out as a character.

Also, the actual politics of the situation. Bassani, the author, was writing post-war, when everything was fresh in his audience’s mind. He was writing a semi-memoir, and he didn’t have to say a lot of things because it was implicit and obvious. But, when you’re writing for Americans in the United States who just like learning about history — particularly if it’s not their own — they know next to nothing about Italy in World War II.

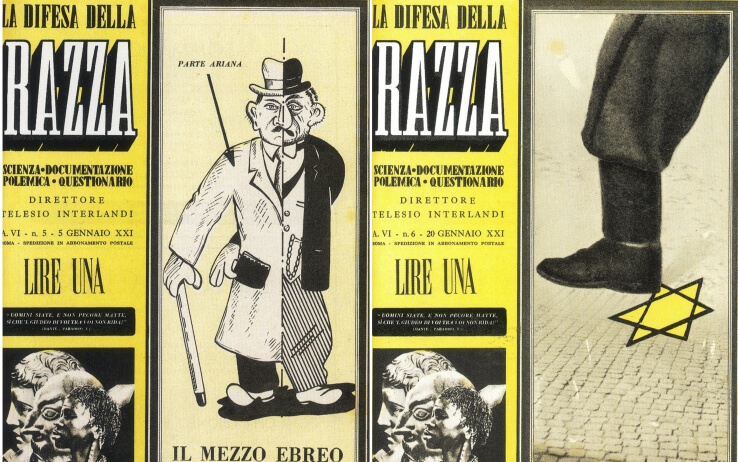

These things have to be understood better, so I found out about the Manifesto della razza, which was the racial laws that Mussolini adopted based on Hitler’s new legislature cracking down on freedom of Jews. And I actually put that into the opera. I did a lot of research on what happened to the Jews in Italy during this period — that was nonfiction research.

I put it in. I felt like I had to. I also had to give the whole thing a framework, so I used the synagogue as a kind of means of departure, beginning with a man who we don’t know very well who arrives at a broken-down synagogue after World War II with a lot of questions on his mind. He takes his journey to the past. The synagogue becomes what it was many years before. We see what happened to him and the entire community. And he leaves with more questions.

I know you’ve worked on several projects with explicitly Jewish themes. Can you tell me what has driven your work in that direction?

I try and write what I understand. I was raised Jewish. My grandparents were orthodox, I was raised conservative, and I continue to observe Jewish holidays and things like that. Though, there was always a distance. I always felt apart from it because of being gay, though I did find the gay synagogue in New York City and I was a member of that.

But the things that always affect me deeply are the things that really happened. When I was a kid, I was a news writer for the Village Voice. And I became an editor. I’ve always been drawn to news, and fact, and reality, and the way it intersects with music and theatre is of great interest to me. Sort of blurring the lines between fiction and fact.

So, this memoir, which does the same thing, coming from a very real place but being fictionalized, appealed to me greatly. So did the whole notion of remembering, which is so important to the Jewish religion. The idea of the Kaddish — keeping people alive through the act of remembering. And this opera is about that. It’s about remembering, and keeping memories alive, and some memories that just will not be forgotten.

I know FINZI was scheduled to premiere before the pandemic. How has the opera evolved over the past two years? How has your relationship to the story changed? Have you learned anything new from the material in the time since the pandemic began?

The opera has gotten — to use the cliche — leaner and meaner.

We wrote it for, perhaps, larger forces than it needed to be told. And I think it’s actually fun for an audience to use their imagination and see actors playing numerous parts, and seeing a set where they’re asked to imagine things more than they are shown them literally, with spectacle. And letting the principals tell the story.

I think that we tightened it up and made it smaller. It’s not small, but it’s not AIDA with elephants. I think it will work particularly well in the theater where it’s premiering — I think it will sound beautiful and be just the right size at the [Edmond J. Safra Hall – home of the National Yiddish Theatre Folksbiene at the Museum of Jewish Heritage].

The pandemic has made everybody look at the unexpected turns of life with fresh eyes. Who expected the twists and turns over the past two years? The fracturing of our society, the conflict between fact and fiction and science and nonsense with what goes on on the internet. And the incredulity of people who see the world through what they believe is a realistic viewpoint watching their neighbors succumb to paranoia and delusion and racism, and change before them. Become something destructive.

I think that we have seen that happening around us, and I think that’s the story of this. These people who believed that they were a part of Italy were suddenly reminded that they may have lived there for generations, but they were not intrinsically Italian. They were Jews. They were not Italian — “What do you MEAN I’m not Italian?” But suddenly, they were being perceived as enemies, their rights being taken away.

We’ve lived through all of that in this country, and had massive demonstrations in the street, and managed to get very little political change on the books despite all of it. State after state has talked about police reform, and not a single one of them has passed it. We’ve had arrant corruption and brutalism in our halls of government, and there’s been a human cry about it, and nothing concrete has been done about it. It seems to be creeping on us.

You know, I was born in a time of activism, and believed that when you went on the street, change was made. And we did make change. And we’re seeing all that change being reversed, and a feeling of despair setting in. The old ways aren’t working, and this virus of the internet has taken over, and it seems unstoppable.

Those are the kind of forces these people are dealing with that are ultimately going to put them on a train to Auschwitz. I’m sorry to be so brutal, but that’s what it’s about. It doesn’t say it right from the beginning, but you get a feeling, and that’s where it goes. I think people will understand that, and hopefully they will understand their own times better by seeing what happened to their grandparents.

Can you talk a little bit about your collaborative relationship with Ricky?

Generally, we both come from a musical theatre background where you sometimes build a piece a scene or a song or a moment at a time. And they are connected by a kind of energy. Musicals work on energy — energy holds them together, and it’s a balancing of that energy. Songs can pump up that energy.

But an opera is continuous. The music that a composer writes for opera works on an emotional level more than it does on energy. You can’t just play louder and bump the lights and strike a pose, and you don’t break for applause. So it must be continuous.

Even though we come from that theatre background, we’re both aware that this is a work that must be continuous. Ricky asks for at least an act before he will begin composing. I have to kind of imagine what the music might sound like. I’ve worked with him long enough to kind of know the things he likes, but also understand that I can put something down. He’ll look at this rather large chunk of it, and he may begin not at the beginning.

He may begin at what he calls a “hot spot.” He’ll find a character that the music seems to spring off the page. He’ll write it, and then he’ll work backwards and forwards from that spot. That’s how he develops leitmotifs, which is so important in opera. It’s a kind of invisible structure that holds the whole composition together.

And then he’ll go back and write the beginning, after he’s figured out a few of these hot spots. We’re also both savvy enough from the theatre to know that you generally don’t begin from page one. If you do, you’re probably going to rewrite page one to ten about 40 times.

So, after the libretto is written, after [Ricky] starts digging in, we change. We’re lucky in that we live a block apart. Ricky likes to wake up at six in the morning and start composing. He has one of these setups where he can play on a midi or a synthesizer with headphones so he doesn’t wake up his neighbors by banging on the piano. By about seven, he’s written something that he’s fallen in love with. He calls me up and says, “You must come over!” And I say, “Can I have coffee first?” He says, “No, I have coffee here. Come right now. You’ve gotta hear this.”

And then we sit there and we listen to it, and then we talk about it. I say, “That’s great, but what about this line? I don’t like the way this line works. Let’s change this, let’s change that, what if that went there?” There’s a lot of sculpting of the clay that goes on, and I think that just comes from our theatrical background. We’re not academics, we don’t write a poetic libretto and slip it through the door and show up on opening night. We work together through the entire process.

I think that is slightly different from the way a lot of operas get written. Ricky gets fuel from the drama, and we also discuss as collaborators the parameters. How far can we go here? Are we telling too much here? Do we need to save this for later? Where do we need a moment of pure, intoxicating beauty? Where do we really need to be gritty and lower the boom? Every moment, every comma, every eighth note gets discussed.

And we have to do that, really, in opera, because in opera what you don’t get is the kind of workshops and readings. I’m doing another new piece at this time called FLYING OVER SUNSET — that had about six workshops and readings. We had only one reading of FINZI-CONTINIS, and it wasn’t really a reading. We did excerpts, because it’s just so much more complicated to get opera singers together who can properly sing the roles than it is to get actors who — if they don’t sing it, then the composer can sing it from the piano, and they can act it. But you can’t do that in opera. You have to actually hear it, so you can only do excerpts. It doesn’t have a bottomless well of finances, and it’s not for profit. So, we have to figure it out and try to make it as watertight as it can before we get into rehearsals. That’s also part of the process.

What’s something that surprised you from the beginning of the writing process to the end?

We tried many different ways to open this opera. I was well into writing when I came up with the idea of the synagogue as an opening, and that was from visiting a synagogue in Amsterdam, actually, that had been used during World War II as a deportation center for Jews.

That did not happen in the synagogue of Ferrara. But I thought that it would work. Bassani began his novel in a graveyard. There was a very famous cemetery in Ferrara. And that’s how we began it.

I did not feel obliged to follow the factual account of the cemetery in Ferrara. The cemetery could be used at the beginning and the end, but it wouldn’t be integral to the rest of the piece. I wanted something that would be a conduit for the entire piece. And the synagogue functioned in that way. It comes in and out of the story at different key moments.

It’s also just an environment that can be projected without a bunch of cumbersome sets moving around, and without having to see a lot of gravestones. It can be done with light — atmospheric light. That’s the best way to listen to music, is to not put up a lot of scenic elements that are rivaling and detracting attention from it — letting music be the environment in which this dramatic work functions.

You talk about deliberateness — every moment carefully chosen. Can you talk about one of those moments in the piece you’re most excited to share with audiences?

There’s a wonderful quartet that they sing — the four principal characters — based on the notion of inexpensive pieces of glass that Micòl Finzi-Contini, the daughter of this legendary family, collects. It’s a little bit like THE GLASS MENAGERIE. These fragile, beautiful pieces of blown glass seem to be a metaphor for their situation.

They sing a quartet that’s full of passion and longing. They each have their own part. Micol’s brother’s Alberto is in the changing room with Malnate, his college roommate, who he’s secretly in love with, and Giorgio is secretly in love with Micòl. And they sing this quartet about the fragility and beauty of glass, which really represents their emotions. I’m looking forward to seeing how that works on a visceral level, a musical level, and also an emotional level.

There is a moment in act two where Giorgio finally says, “Why won’t you love me?” And she just lowers the boom, and says, “You do not sexually arouse me. I am not aroused by making love to someone who could be my brother.” And we realize the difference between them, that his father always warned about, which was that the Finzi-Continis are Jew who don’t really like Jews. They are so much a part of the Italian culture that they’ve forgotten their roots, and they don’t understand persecution — they are so far above it.

She’s not sexually aroused by him, and it’s a very cruel scene. But then there’s a moment of sort of redemption for her, where after she gets him out and tells him never to come back, we realize that she, of all that family, sees what’s coming more than anyone else. She knows that, were he to be with her, he would be unsafe. Because she is a target for Mussolini and fascism to attack. She’s a symbol, and she’s going to be deported. So basically, she has told him: get lost, I am not turned on by you. And then she says, now you’re free, and I will never be free.

She also has a fatalistic attitude about it right from the beginning, where she sings about her garden, and compares herself to trees — trees that are immovable, rooted to the ground in which they live. I think she says that she’s both rooted to the ground and reaching for the sky. And she doesn’t feel she can ever leave this garden.

I’m very interested to see how those moments work.

I’m getting chills just thinking about it.

The Garder of The Finzi-Continis

January 27 – February 6, 2022

More information and tickets HERE